The Best Engineers Think Like Investors, Not Builders

Your approach matters more than the technical details

I lived in the library during college.

“The more textbook theory I studied, the better an engineer I would become,” I thought.

Yet when I started working, I noticed that the best engineers in the industry didn’t necessarily know more theory than new grads. They just brought a different mindset, the investor’s mindset, to work.

It was this mindset that helped them ask smarter questions, prioritize better, and set themselves apart. Like an investor they:

focused on work that paid off sooner than later

calculated if the work was worth their time or not before diving into it

weighed the opportunity costs of their work

In this article, I discuss 3 common problems every engineer will face in their career, and how the investor’s mindset will help you make the right technical decision every time.

1. When will your work payoff?

In investing, there’s a concept called the “time value of money.” This refers to the fact that money now is worth more than money later. You’d rather have an investment pay off one year from now rather than five years from now.

Engineering work has “time value” as well. Engineering projects that payoff now are worth more than engineering projects that payoff later.

We saw this recently with Facebook stock. It dipped by 50% from its all-time highs when executives revealed their Metaverse investments might not pay off for as long as “15 years later.”

Meta invested over $10B into it already too.

Just as how the long payoff period of the metaverse spooked investors, engineers should avoid work that pays off too far into the future. This mistake happens particularly when it comes to engineering migrations.

Why Migrations Are Costlier Than You Think

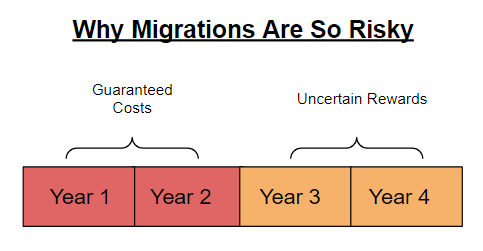

From an investment standpoint, engineering migrations are a guaranteed upfront cost, for uncertain rewards in the future. And these rewards don’t pay off for longer than most people realize.

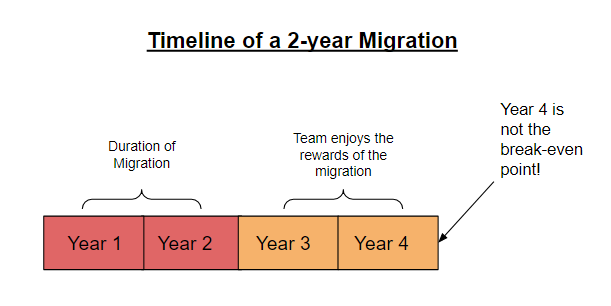

Consider the timeline of a two-year migration below.

The cost is guaranteed, but the rewards are not.

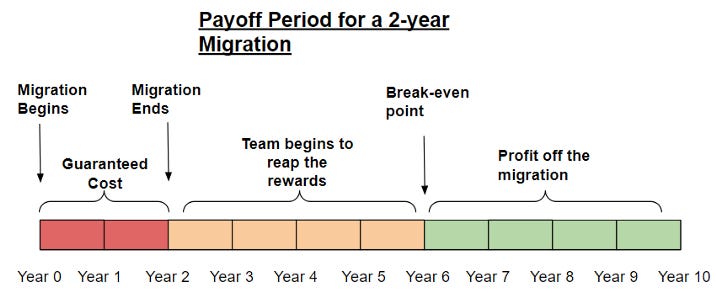

First, the two years we spend migrating now are worth more than the two years we benefit from the migration later. So the break-even point for a migration is longer than four years later.

Second, the rewards of any migration must exceed the cost of the work. It doesn’t make sense to spend two years to save two years. You might as well not do the migration at all then.

You should discount the rewards in years 3 and 4 because it is in the future.

I have a rule that any engineering work must have a minimum of 2x of the rewards to justify the cost. If I spend a month migrating, it has to save me two months of time to payoff.

With this rule, if you spend two years on an engineering migration, you must enjoy the benefits for double the migration time to break even.

Thus, the break-even point for a 2-year migration is actually four years later — or six years from the beginning of the migration.

Are you willing to wait 6 years to see the payoff of a 2-year migration?

The longer a migration takes, the greater the risk that it may never pay off. Other risks include:

Changing business priorities— The company might deprecate the team’s service, rendering the migration obsolete.

Exit risks — If a startup gets acquired, these migrations won’t affect the valuation of the startup, and thus delivers zero-business value.

Execution Risks — A single execution mistake (eg a data leak) could nullify all rewards of the migration.

The lesson is that engineering should bias toward projects that payoff sooner than later, or risk never seeing the rewards at all.

2. Is this project worth your time?

Warren Buffett once said that a company’s returns are “far more a function of what business boat you get into than it is of how effectively you row.”

The same principle applies to engineering. Working on the right project (getting in the right boat) is more important than the details of the code you write (how hard you row).

This is particularly important when it comes to buy vs. build decisions in engineering.

Although I admit I get excited by greenfield projects, it’s important to not dive right in and default to “build.” Like an investor doing due diligence, engineering must calculate the costs and benefits before deciding to go either way.

Some questions I ask to decide this include:

If we purchased a solution, how easy is it to integrate and maintain?

Is this feature a core competency of the company?

How expensive is it to build this at all?

With this last question — it’s important to estimate the costs of any “build” proposal to make sure the expected rewards are proportional to the engineering effort. One way to establish a baseline for this is to:

Estimate how many hours a project will take.

Multiply this by your hourly engineering rate.

Use this as a guideline for the cost of a project.

The deeper into the blue or red zone a project is, the more compelling the decision to build or buy respectively.

While cost is not the only consideration, sometimes doing this exercise alone can help engineering decide which path to take.

Example: Buy vs. Build with RecordJoy.com

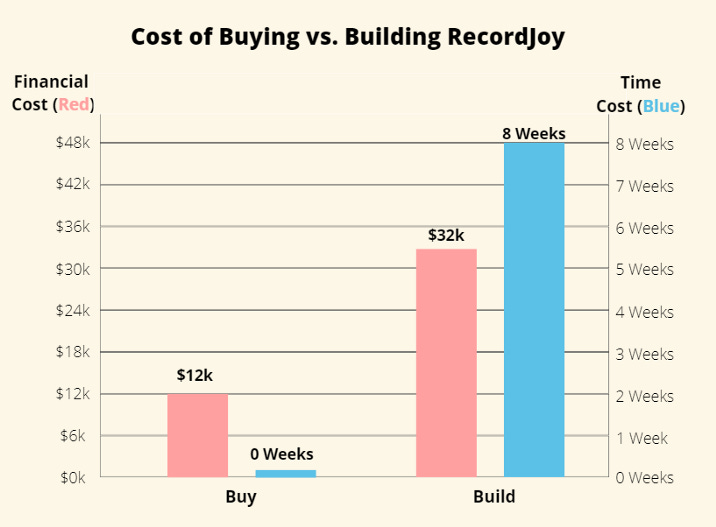

I came across this decision myself when my business partner and I had the choice to buy a screen-recording website called RecordJoy.com for $12,000 or build it from scratch.

Screenshot of RecordJoy.com when we bought it

We estimated that it would take us two months to build the website ourselves, or 320 engineering hours. Assuming our time was worth $100/hour, it would cost $32k to build ourselves.

The choice to buy RecordJoy then boiled down to whether we’d rather spend $12k to buy RecordJoy now, or $32k building it ourselves. It was cheaper to buy the website than to build it, so we bought the website.

Building RecordJoy from scratch is much more expensive than buying it.

Looking back, this decision was the most important engineering decision that we made while working on RecordJoy. It allowed us to focus our energy on building paid features rather than the product itself.

It also reduced the engineering risk. By buying RecordJoy, we had a guaranteed product we could use immediately vs. a product that we have no guarantees of finishing two months from now.

As for RecordJoy, we grew this company from no revenue to $700 a month in recurring revenue with a few months of work. We sold the company on Microacquire.com in April 2022.

Microacquire sent me a gift congratulating me after I sold my company on their website.

3. Will this project move the company needle the most?

In investing, there’s another concept called “opportunity cost.” Opportunity cost is what you give up when you make a choice.

For example, if I wanted dessert and had the choice between cake and ice cream, the cost of choosing cake isn’t just what you paid. The cost of cake is the foregone opportunity of enjoying the ice cream as well. So with every choice, one door opens and another closes.

Every technical debt cleanup has an opportunity cost too. Cleaning up one system means we can’t cleanup another. So it’s critical to make sure that the cleanup we work on drives the most impact.

I compare managing technical debt to that of cleaning a house. Just as how your house will never be fully clean, it’s impossible to fully eliminate technical debt. However, some rooms in your house are more important to clean than others.

Why clean the garden if the inside of the house isn’t clean?

Why clean the guest bedroom if the main bedroom isn’t clean?

A clean guest bedroom

Similarly, some technical debt helps the team move faster than others.

The alerting system for a billing service is more impactful than the alerting for an internal tool. The testing infrastructure for the homepage is more important than for any other page.

The lesson for engineers is to always consider the opportunity costs of your work.

Don’t clean your guest bedroom until your main bedroom is clean first!

Example: Doma’s Migration from Heroku to Azure

Doma, a real-estate software company, had a technical debt cleanup recently where their focus on cleaning the main bedroom paid off.

To prepare for their IPO in 2021, they had to migrate their cloud infrastructure from Heroku to Microsoft Azure. They gave themselves half a year to plan and execute on this migration.

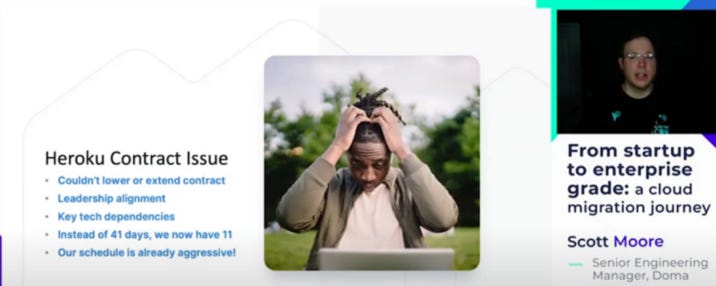

However, towards the end, Doma had an issue with their contract with Heroku. Heroku wouldn’t allow them to renew their contract at a lower volume, and only presented Doma with the option of another longer-term contract. So if Doma didn’t complete the migration to Azure in time, they could have their cloud infrastructure cut off.

They gave themselves 41 days to execute the migration, but this issue cut their timeline down by a month, down to 11 days.

A slide from Doma’s presentation on their migration to Azure.

Considering their contract with Heroku had an imminent deadline, not completing this migration could cost the company millions of dollars. Any other engineering work paled in comparison to the impact of not completing this migration in time.

In response, Doma issued an all-hands on deck for their engineering teams. Every team had to prioritize migrating off of Heroku because the opportunity cost of this migration was too high. Doing any other work would be the equivalent of cleaning the guest bedroom, when the main bedroom, the Heroku migration, was on fire.

Doma’s focus paid off. They migrated all of their remaining apps to Azure in 8 days—with 3 days to spare for testing. Their investor mindset allowed them to weigh the opportunity cost of the migration vs. other work and avert a crisis. They IPO’d soon after.

Final Thoughts

In engineering, developing the investor mindset will get you further than knowing the latest tech fad.

If you spend more time considering 1) the financial costs 2) the payoff periods and 3) the opportunity costs of your work, you will make better technical decisions and save time.

💡 If You Liked This Article...

I publish a new article every Tuesday with actionable ideas on entrepreneurship, engineering, and life.